This post provides an overview of An Essay on Criticism by Alexander Pope.

AN OVERVIEW OF AN ESSAY ON CRITICISM

~BY ALEXANDER POPE

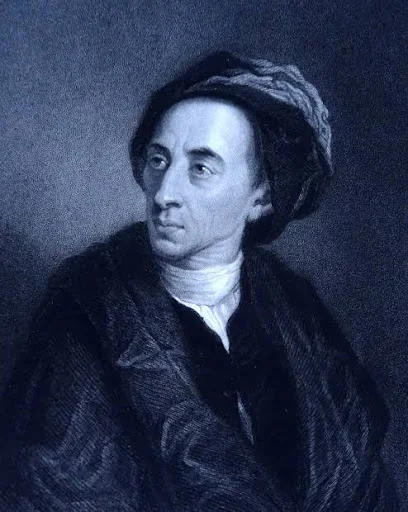

Alexander Pope was born in the year 1688, during the year of revolution in London. He in many respects was a unique figure of the English literary history. Firstly, because he was considered to be “the poet” of a great nation. He was an undisputed master in the narrow field of satiric and didactic verse during the early 18th century. Pope’s influence completely dominated the poetry of his age. Many foreign writers looked to him and many English poets looked to him as their inspiration. Secondly, he was one of the writers who was a remarkable reflection of the spirit of the age he lived in. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Thirdly, he was the one and only important writer of the age who gave his whole life to letters. Unlike Swift, Addison and other writers of his age, Pope was someone who chose only literature as his profession. And fourthly, by the sheer force of his ambition he won his place, and held it, in spite of religious prejudice, and in the phase of physical and temperamental obstacles that would have discouraged a stronger man. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Criticism” is perhaps the clearest statement of neoclassical principles in any language. Pope in this essay, not only gives the scope of good literary criticism, but he also redefines classical virtues in terms of ‘nature’ and ‘wit’ as necessary to both poetry and criticism. “An Essay on Criticism” was first published anonymously through an obscure book seller. Now, coming to Neoclassicism, it is basically a political and philosophical movement that developed during the age of enlightenment. One of the main characteristics of neoclassicism was decorum. But, the central tenant was the imitation of nature. This was to be achieved by artist modelling their work on the ancients.

Thus, the poets and dramatist were less interested in new forms than in inventing the new forms and were more into imitating the old ones of epic, eclogue, epigram, elegy, ode, satire, comedy, tragedy and so on. Indeed an awareness of the characteristics of each genre, and their relation to one another, was an integral feature of the neoclassicism. The neo-classicists were often termed as traditionalists, and they believed that literature was an art to be perfected by discipline, vigorous study and continuous practice. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

“An Essay on Criticism” is written in verse, in the form of Horace’s Ars Poetica. It sums up the art of poetry as first taught by Horace and then Boileau and the 18th century classicists. Though written in Heroic couplets, we hardly consider this is a poem but rather a storehouse of critical maxims.

Alexander Pope in his “An Essay on Criticism” calls for a “return to nature” is complex. On the cosmic level Nature signifies the convenient order of the world and the universe, a hierarchy in which each entity has a proper assigned place of its own. Nature can refer to what is central, common and universal to all human experience, encompassing the spheres of morality and knowledge. It also signifies the rules of proper moral conduct as well as archetypal or representative patterns of human reason. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

It means having qualities that makes someone one of a kind. Nature for him is thus, is a universal and general regulation that beyond human beings control or grasp but is indispensable in influencing their literary creation. It seems more of a divine source of inspiration or a sort of sacred rules than personal skills or individual talent. Pope says that Nature has the capability to render “life, force and beauty” to an art. Literary creation and appreciation is redefined and regulated by Nature. Nature constitutes and functions as “the Source, and End, and Text of art”. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

To acquire a better judgement and redefined taste of Literature depends on Nature, which is “just”, “unerring”, “divinely bright”, “clear” and “universal”. Any art that fails to reflect nature is not worth to be called an art at all. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

In the essay “An Essay on Criticism”, Pope puts a great emphasis on the word “Wit”. The word wit in Pope’s time could refer in general to intelligence, it also meant in the modern sense of cleverness, as expressed in figures of speech and especially discerning unanticipated similarities between different entities. Wit according to Pope is the general ability of a writer to express the truth and morality. According to Pope, wit is the reflection of imitation. True wit, exists in the relationship among ideal image and expression. Wit is like an everlasting sea. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s exploration of wit lines up with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with Nature: “True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/ What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest” (297-298). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope subsequently says that expression is the “Dress of Thought” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them. The lines above are concentrated expressions of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

While Pope says that the good poets makes the best critics, and while he notice that some critics are failed poets, he points out that both the best poetry or the best criticism are divinely inspired: “Both must alike from Heav’n derive their Light” (13-14). Pope sees the endeavour of criticism as a noble one, provided it abides by Horace’s advice for the poet:

"But you who seek to give and merit Fame,

And just bare a Critick’s noble Name,

Be sure your self and your own Reach to know,

How far your Genius, Taste, and Learning go

Launch not beyond your Depth... (46-56)"

Apart from knowing his own capacities, the critic must also be fully familiar with every aspect of the author whom he/she is examining. Pope suggests the critic that he base his interpretation on the author’s intention: “In ev’ry Work regard the Writer’s End, / Since none can compass more than they Intend”. (233-234, 255-256). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope notes down two other guidelines to be followed by the writers and the critics. The first is to recognize the overall unity of a work and thereby to avoid falling into partial assessments based on the writer’s use of poetic, conceits, ornamented language, meters as well as judgements which are biased towards either archaic or modern styles or based on the reputations of given writers. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope, finally advices that a critic needs to possess a moral sensibility, as well as a sense of balance and proportion, this he indicates in the lines: “Nor in the Critick let the Man be lost! / Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join” (523-525). (An Overview of An Essay of Criticism)

Pope then, ends his advice with a summary of an ideal critic:

"But where’s the Man, who counsel can bestow,...

And Love to Praise, with Reason on his Side? (631-642)"

The qualities of a good critic are primarily attributes of humanity or moral sensibility rather than aesthetic qualities. Indeed, the only specifically aesthetic quality mentioned here is “taste”. The remaining virtues might be said to have theological ground, resting on the ability to overcome pride. Pope effectively transposes the language of theology (“soul” and “pride”). The reason to which Pope appeals is (as in Aquinas and many medieval thinkers) a universal representation in human nature, and is a result of humility. It is thus, a disposition of humility – an aesthetic humility, if you will – which enables the critic to avoid the foregoing faults. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Now, Pope goes on to provide advice to both poet and critic. The utmost important advice here is to “follow Nature,” whose restraining function he explains:

"Nature is all fix’d the Limits fit,

And wisely curb’d proud Man’s pretending Wit;

... One Science only will one Genius fit;

So vast is Art, so Narrow Human Wit ... (52 – 53)"

Pope, designates human wit generally as an instrument of Pride. He, however, clarifies that in the scheme of nature, man’s wit finds an appropriate place. It is in this context Pope says that:

"First follow NATURE, and your Judgement frame

By her just Standard, which is still the same;

Unerring Nature, which is still divinely bright,

Once clear, unchang’d and Universal Light,

Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart,

At once the Source, and End, and Test of Art." (68 – 73) (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope unlike other medieval rhetoricians, does not entirely believes that poetry is a rational process. He seems to assert the primacy of wit over judgement, of art over criticism, viewing art as inspired and as transcending the norms of conventional thinking in its direct appeal to the heart. The critic’s task here as Pope suggests, is to recognize the superiority of great wit. While these emphasis strides beyond many medieval and Renaissance aesthetics, it must of course be read in its own poetic context. He warns the writers and authors that should not just rely on their own insights but draw on the common store of poetic wisdom, established by the ancients. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s exploration of wit lines up with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with Nature: “True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/ What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest” (297-298). Pope subsequently says that expression is the “Dress of Thought” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them. The lines above are concentrated expressions of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

The poet’s task here is twofold: not only to find the expression that will most truly convey nature, but to ensure that the substance he is expressing is indeed a natural insight or thought.

Another classical ideal urged by Pope is that of organic unity and wholeness. The expression or style must be suited to the subject matter and meaning: “The Sound must seem an Echo to the Sense ” (365)

Pope advices both Poet and critic to follow the Aristotelian ethical maxim: “Avoid Extremes”. For those who excess in any direction display “Great Pride, or Little Sense” (384 – 387). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Indeed the central passage in “An Essay on Criticism”, as in the later “Essay on Man”, Pope views all the major faults as stemming from pride. It is pride which leads critics and poets to overlook universal truths in favour of subjective whims: pride which cause them to value only certain parts but not the whole, which disables them to attain a harmony between wit and judgement, and pride which underlies their excesses and biases. (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s final strategy in “An Essay on Criticism” is to equate the classical literary and critical traditions with nature, and to sketch a redefined outline of literary history from classical times to his own era. Pope insists that the rules of nature were merely discovered, not invented, by the ancients: “Those Rules of old discover’d, not devis’d, / Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d” (88-89). (An Overview of An Essay on Criticism)

Pope’s advice for both critic and poet is clear: “Learn hence for Ancient Rules a just Esteem; / To copy Nature is to copy Them” (139 – 140). Pope traces the genealogy of “nature”, as embodied in classical authors.

When was An Essay on Criticism published?

What does Pope say about Nature?

It means having qualities that makes someone one of a kind. Nature for him is thus, is a universal and general regulation that beyond human beings control or grasp but is indispensable in influencing their literary creation. It seems more of a divine source of inspiration or a sort of sacred rules than personal skills or individual talent. Pope says that Nature has the capability to render “life, force and beauty” to an art. Literary creation and appreciation is redefined and regulated by Nature. Nature constitutes and functions as “the Source, and End, and Text of art”. To acquire a better judgement and redefined taste of Literature depends on Nature, which is “just”, “unerring”, “divinely bright”, “clear” and “universal”. Any art that fails to reflect nature is not worth to be called an art at all.

What did Alexander Pope say about "Wit"?

Pope’s exploration of wit lines up with the central classical virtues, which are themselves equated with Nature: “True Wit is Nature to Advantage drest,/ What oft was Thought, but ne’er so well Exprest” (297-298).

Pope subsequently says that expression is the “Dress of Thought” and that “true expression” throws light on objects without altering them. The lines above are concentrated expressions of Pope’s classicism. If wit is the “dress” of nature, it will express nature without altering it.

What advice did Pope give to critics and poets in his essay "An Essay on Criticism"?

But you who seek to give and merit Fame,

And just bare a Critick’s noble Name,

Be sure your self and your own Reach to know,

How far your Genius, Taste, and Learning go:

Launch not beyond your Depth... (46-56)

Apart from knowing his own capacities, the critic must also be fully familiar with every aspect of the author whom he/she is examining. Pope suggests the critic that he base his interpretation on the author’s intention: “In ev’ry Work regard the Writer’s End, / Since none can compass more than they Intend”. (233-234, 255-256).

Pope notes down two other guidelines to be followed by the writers and the critics. The first is to recognize the overall unity of a work and thereby to avoid falling into partial assessments based on the writer’s use of poetic, conceits, ornamented language, meters as well as judgements which are biased towards either archaic or modern styles or based on the reputations of given writers.

Pope, finally advices that a critic needs to possess a moral sensibility, as well as a sense of balance and proportion, this he indicates in the lines: “Nor in the Critick let the Man be lost! / Good-Nature and Good-Sense must ever join” (523-525). (An Overview of An Essay of Criticism)

Pope then, ends his advice with a summary of an ideal critic:

But where’s the Man, who counsel can bestow,

...

And Love to Praise, with Reason on his Side? (631-642)

The qualities of a good critic are primarily attributes of humanity or moral sensibility rather than aesthetic qualities. Indeed, the only specifically aesthetic quality mentioned here is “taste”. The remaining virtues might be said to have theological ground, resting on the ability to overcome pride. Pope effectively transposes the language of theology (“soul” and “pride”). The reason to which Pope appeals is (as in Aquinas and many medieval thinkers) a universal representation in human nature, and is a result of humility. It is thus, a disposition of humility – an aesthetic humility, if you will – which enables the critic to avoid the foregoing faults.

Now, Pope goes on to provide advice to both poet and critic. The utmost important advice here is to “follow Nature,” whose restraining function he explains:

Nature is all fix’d the Limits fit,

And wisely curb’d proud Man’s pretending Wit;

... One Science only will one Genius fit;

So vast is Art, so Narrow Human Wit ... (52 – 53)

Pope, designates human wit generally as an instrument of Pride. He, however, clarifies that in the scheme of nature, man’s wit finds an appropriate place. It is in this context Pope says that:

First follow NATURE, and your Judgement frame

By her just Standard, which is still the same;

Unerring Nature, which is still divinely bright,

Once clear, unchang’d and Universal Light,

Life, Force, and Beauty, must to all impart,

At once the Source, and End, and Test of Art. (68 – 73)

Pope unlike other medieval rhetoricians, does not entirely believes that poetry is a rational process. He seems to assert the primacy of wit over judgement, of art over criticism, viewing art as inspired and as transcending the norms of conventional thinking in its direct appeal to the heart. The critic’s task here as Pope suggests, is to recognize the superiority of great wit. While these emphasis strides beyond many medieval and Renaissance aesthetics, it must of course be read in its own poetic context. He warns the writers and authors that should not just rely on their own insights but draw on the common store of poetic wisdom, established by the ancients.

The poet’s task here is twofold: not only to find the expression that will most truly convey nature, but to ensure that the substance he is expressing is indeed a natural insight or thought.

Another classical ideal urged by Pope is that of organic unity and wholeness. The expression or style must be suited to the subject matter and meaning: “The Sound must seem an Echo to the Sense ” (365)

Pope advices both Poet and critic to follow the Aristotelian ethical maxim: “Avoid Extremes”. For those who excess in any direction display “Great Pride, or Little Sense” (384 – 387).

Indeed the central passage in “An Essay on Criticism”, as in the later “Essay on Man”, Pope views all the major faults as stemming from pride. It is pride which leads critics and poets to overlook universal truths in favour of subjective whims: pride which cause them to value only certain parts but not the whole, which disables them to attain a harmony between wit and judgement, and pride which underlies their excesses and biases.

Pope’s final strategy in “An Essay on Criticism” is to equate the classical literary and critical traditions with nature, and to sketch a redefined outline of literary history from classical times to his own era. Pope insists that the rules of nature were merely discovered, not invented, by the ancients: “Those Rules of old discover’d, not devis’d, / Are Nature still, but Nature Methodiz’d” (88-89).

READ NOW

https://literarysphere.com/summary-of-upon-westminster-bridge-poem/(opens in a new tab)

0 Comments